Permafrost is ground that remains frozen for at least two consecutive years. It is composed of soil, rocks, sand, and organic material bound together by ice. Permafrost is mostly found in high-latitude regions such as Siberia, Alaska, Canada, and Greenland, as well as high mountain areas. Beneath its surface lies a vast archive of ancient ecosystems, including frozen plants, microbes, and even animal remains.

Formation of Permafrost

Permafrost formed thousands of years ago during ice ages when colder climates caused soil and water to freeze permanently. Over time, these frozen layers accumulated and stabilized, covering about 24% of the land area in the Northern Hemisphere. The depth of permafrost varies from a few meters to more than 1,500 meters in Siberia, depending on climate and geology.

Structure of Permafrost

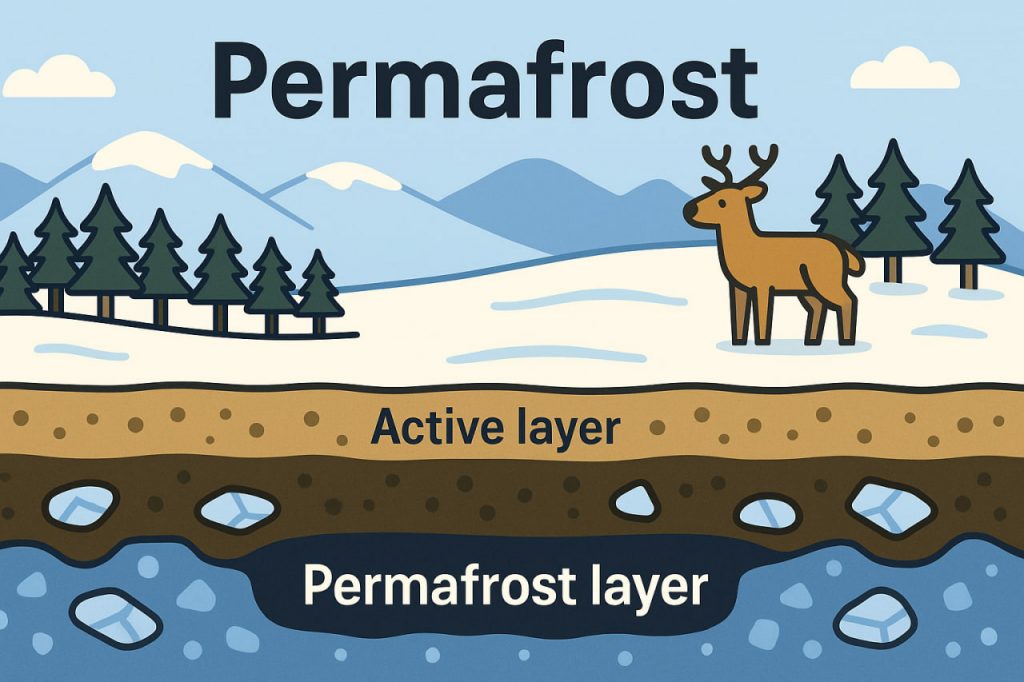

Permafrost consists of two main layers:

- Active layer – the top soil that thaws in summer and refreezes in winter, supporting vegetation.

- Permafrost layer – permanently frozen ground below the active layer.

This structure makes permafrost unique, as it traps water and organic matter for thousands of years.

Ecological Role

Permafrost is crucial for ecosystems and climate regulation. It stores enormous amounts of carbon in the form of frozen plant material. When stable, it helps maintain landscapes like tundras, wetlands, and boreal forests. Permafrost also influences hydrology, as thawing can create lakes, rivers, or swamps. Many Arctic animals and plants have adapted to these conditions.

Climate Change and Permafrost Thaw

Global warming threatens the stability of permafrost. Rising temperatures cause it to thaw, releasing greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere. This creates a feedback loop, where thawing accelerates climate change. Additionally, thawing destabilizes soils, leading to landslides, collapsing infrastructure, and changes in ecosystems.

Human Impact and Challenges

Communities living in permafrost regions face unique challenges. Thawing ground damages roads, pipelines, and buildings, increasing risks for people in northern settlements. At the same time, permafrost preserves archaeological and paleontological remains, offering insights into ancient life. Balancing human development with permafrost conservation is an urgent issue in Arctic regions.

Conclusion

Permafrost is not just frozen ground but a critical part of Earth’s climate system and history. Its stability regulates carbon storage, ecosystems, and human activity in northern regions. With global warming accelerating thawing, protecting and monitoring permafrost is essential to reducing climate risks and preserving this unique natural heritage.

Glossary

- Permafrost – ground frozen for at least two consecutive years.

- Active layer – surface soil above permafrost that seasonally thaws.

- Carbon storage – trapped organic matter holding carbon in frozen soils.

- Methane – potent greenhouse gas released from thawing permafrost.

- Feedback loop – process where thawing increases warming, causing more thawing.

- Tundra – cold, treeless ecosystem typical of permafrost areas.