Earthquakes are among the most powerful and unpredictable natural phenomena on our planet. They are caused by the sudden release of energy accumulated in Earth’s crust, resulting in seismic waves that shake the ground. While most earthquakes are small and go unnoticed, the largest ones can devastate cities, trigger tsunamis, and reshape entire landscapes. Understanding how earthquakes occur and the different types that exist helps scientists assess risks and protect communities in vulnerable regions.

How Earthquakes Occur

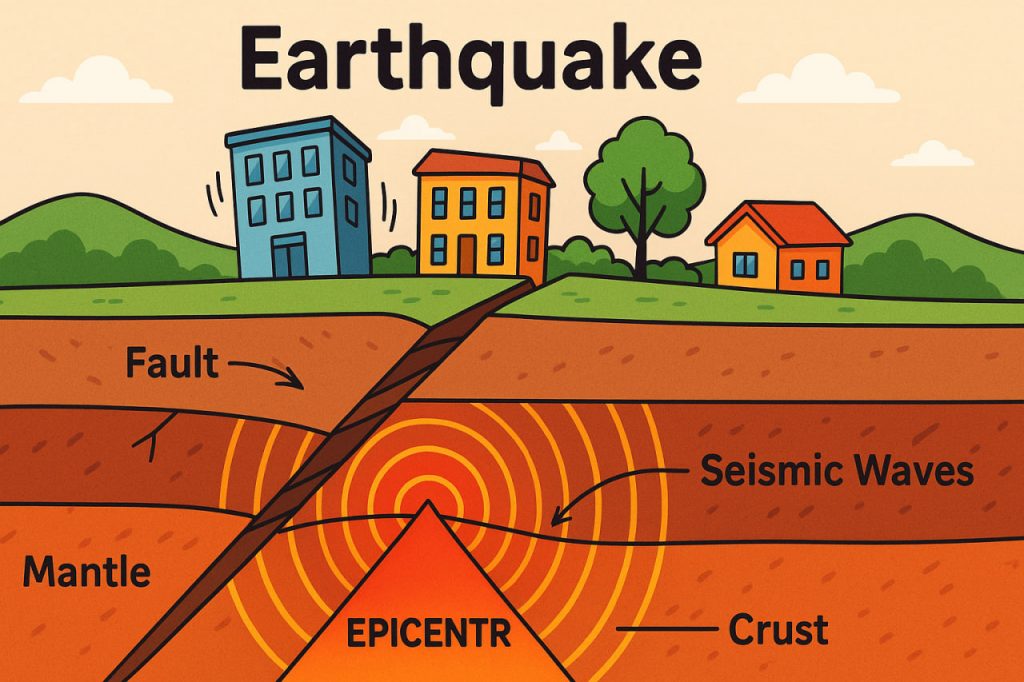

Beneath Earth’s surface, the crust and upper mantle are divided into massive pieces called tectonic plates. These plates are constantly moving—colliding, sliding past, or pulling away from each other—at rates of a few centimeters per year. Over time, stress builds up along the boundaries where they meet, especially at fault lines, until the rock can no longer withstand the pressure. When that stress is released, it sends shock waves through the Earth, producing what we experience as an earthquake. The point within the Earth where the rupture begins is called the focus (or hypocenter), and the spot directly above it on the surface is the epicenter—the place where shaking is usually strongest.

The Role of Seismic Waves

When an earthquake occurs, energy travels through the Earth in the form of seismic waves. The first to arrive are P-waves (primary waves), which compress and expand material in the direction they travel, moving very quickly through both solid and liquid layers. Next come S-waves (secondary waves), which move the ground side to side and are more destructive. Surface waves, which travel along the crust, cause the most visible damage—making buildings sway, bridges buckle, and soil liquefy. The combination of these waves determines the earthquake’s overall impact, and their analysis allows scientists to locate the epicenter and measure its strength.

Types of Earthquakes

Earthquakes can be classified in several ways depending on their origin and geological environment:\n\n1. Tectonic Earthquakes – The most common type, caused by the movement of tectonic plates. These include:\n – Strike-slip earthquakes, where plates slide horizontally past one another (e.g., the San Andreas Fault in California).\n – Normal-fault earthquakes, where plates move apart and one block slips downward, common in rift zones.\n – Reverse or thrust earthquakes, where plates collide and one is pushed over the other, typical in subduction zones such as Japan or Chile.\n\n2. Volcanic Earthquakes – Occur near volcanoes as magma rises, cracking the surrounding rock. These often precede eruptions and serve as early warning signs.\n\n3. Collapse Earthquakes – Small tremors caused by the collapse of underground cavities, such as caves or mines.\n\n4. Explosion-Induced Earthquakes – Artificial seismic events resulting from human activities like nuclear tests or large industrial explosions.\n\nEach type offers valuable information about the geological processes shaping our planet.

Measuring Earthquakes

To quantify earthquakes, scientists use two key measurements: magnitude and intensity. Magnitude, measured by the Richter scale or the modern moment magnitude scale (Mw), indicates the total energy released. Intensity, often described by the Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale, measures how strongly the ground shakes and how much damage occurs at specific locations. For instance, a magnitude 6.0 earthquake can feel weak in rural areas but be devastating in densely populated cities depending on soil type, depth, and construction quality.

Global Distribution and Patterns

Earthquakes are not randomly distributed—they mostly occur along plate boundaries. The most seismically active region is the Pacific Ring of Fire, encircling the Pacific Ocean. This zone includes Japan, Indonesia, New Zealand, and the west coasts of North and South America. Other notable zones include the Himalayan Belt and the Mediterranean-Asian region. Intriguingly, minor quakes can also occur far from boundaries due to the reactivation of ancient faults. Mapping these patterns helps scientists predict long-term risks, though exact predictions remain impossible.

Effects and Consequences

The impacts of earthquakes vary dramatically. Small tremors may cause little more than vibrations felt indoors, while major quakes can destroy infrastructure, alter river courses, and generate tsunamis. Secondary effects like fires, landslides, and soil liquefaction often cause more damage than the shaking itself. In modern urban centers, strict building codes and early warning systems can save thousands of lives, demonstrating how knowledge of seismology transforms disaster into resilience.

Interesting Facts

- The deepest earthquakes occur more than 600 kilometers below the surface in subduction zones.

- Earthquakes can permanently shorten the day by slightly altering Earth’s rotation.

- The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake in Japan moved the entire country several meters eastward.

- More than 80% of all major earthquakes occur along the Pacific Ring of Fire.

- Some animals, like dogs and elephants, are believed to sense seismic vibrations seconds before humans do.

Glossary

- Tectonic Plate – A massive slab of Earth’s lithosphere that moves over the mantle.

- Fault Line – A fracture in the Earth’s crust where blocks of rock move relative to each other.

- Focus (Hypocenter) – The underground point where an earthquake begins.

- Epicenter – The surface point directly above the earthquake’s focus.

- Seismic Waves – Energy waves that travel through Earth’s layers during an earthquake.

- Magnitude – A measure of the total energy released during an earthquake.

- Intensity – A description of the earthquake’s effects on people, structures, and the surface.

- Subduction Zone – A region where one tectonic plate slides beneath another.

- Liquefaction – The process in which saturated soil loses strength and behaves like a liquid during shaking.

- Ring of Fire – A seismically active zone encircling the Pacific Ocean known for frequent earthquakes and volcanoes.