Earth’s magnetic field is not fixed or perfectly stable, even though it often feels constant in everyday life. One of the most intriguing manifestations of this instability is the drift of the magnetic poles, a slow but measurable movement that has been accelerating in recent decades. Unlike the geographic poles, which are defined by Earth’s rotation axis, magnetic poles are generated by complex processes deep within the planet’s core. As molten iron moves beneath the crust, it reshapes the magnetic field, causing the magnetic poles to wander across the planet’s surface. This drift affects navigation systems, animal migration, and scientific models used to understand Earth’s interior. Studying magnetic pole drift provides critical insight into the dynamic processes occurring thousands of kilometers beneath our feet.

What Causes the Magnetic Pole to Drift

The drift of the magnetic pole is driven by Earth’s geodynamo, a process occurring in the liquid outer core composed mainly of molten iron and nickel. As this electrically conductive fluid moves due to heat and Earth’s rotation, it generates magnetic fields through complex electromagnetic interactions. These flows are not uniform; they change over time, creating fluctuations in magnetic intensity and direction. When certain regions of the core strengthen or weaken, they pull the magnetic pole in different directions. According to geophysicist Dr. Laura Henderson:

“The magnetic pole moves because Earth’s core is alive with motion.

Every shift reflects changes in deep, invisible currents far below the surface.”

This means magnetic pole drift is not random, but a natural outcome of constantly evolving core dynamics.

Observed Changes in Magnetic Pole Movement

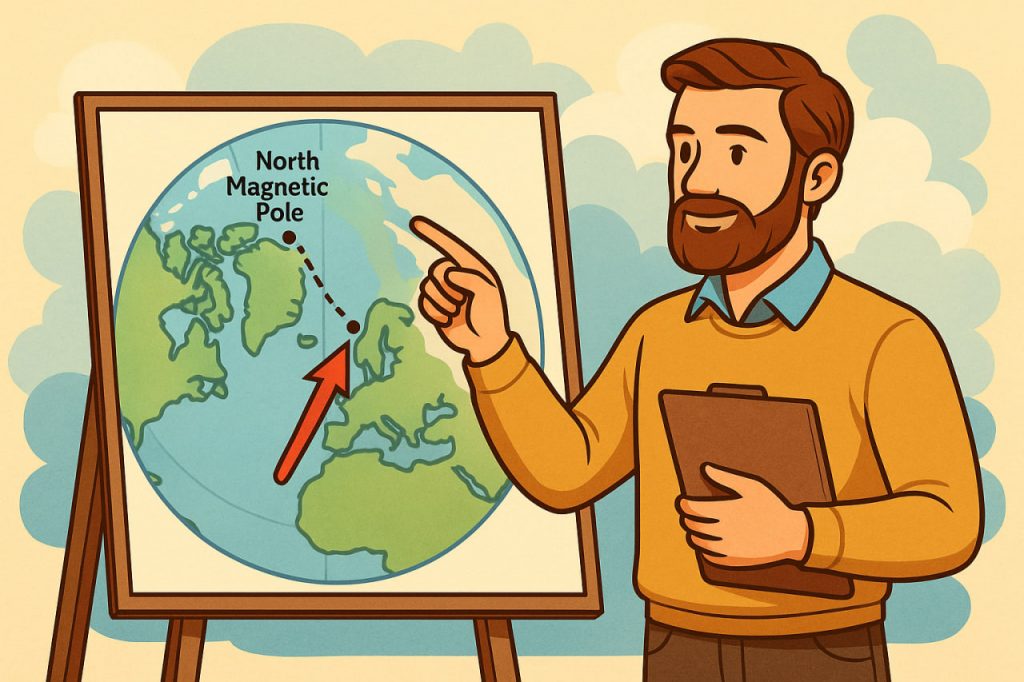

For much of the 20th century, the North Magnetic Pole drifted slowly, moving only a few kilometers per year. However, since the 1990s, scientists have observed a dramatic acceleration, with speeds exceeding 50 kilometers per year at times. The pole has migrated from northern Canada toward Siberia, forcing researchers to frequently update magnetic models used in navigation. Satellite missions such as ESA’s Swarm constellation have allowed scientists to track these changes with unprecedented precision. These observations confirm that the magnetic field is becoming increasingly asymmetric, reflecting powerful changes in the flow patterns of Earth’s core.

Impacts on Navigation and Technology

Magnetic pole drift has practical consequences for modern technology and navigation. Aircraft, ships, and submarines rely on magnetic references as backups to satellite-based systems. Runways at major airports are periodically renumbered when magnetic north shifts enough to alter compass headings. Smartphones, GPS calibration systems, and surveying equipment also depend on accurate magnetic models. While these technologies are designed to adapt, rapid changes require more frequent updates to avoid errors. Scientists emphasize that magnetic drift does not pose an immediate danger, but it highlights the importance of continuous monitoring and adaptive systems.

Magnetic Drift vs. Magnetic Reversal

It is important to distinguish magnetic pole drift from a full magnetic field reversal, where north and south magnetic poles completely swap positions. Drift occurs continuously and does not imply an imminent reversal. Geological records show that reversals happen irregularly, roughly every few hundred thousand years, and take thousands of years to complete. Current evidence suggests that while Earth’s magnetic field has weakened slightly, it remains stable enough to protect the planet from solar radiation. Researchers continue to study whether present-day changes represent normal variability or early signs of larger transitions.

Why Magnetic Pole Drift Matters for Science

Beyond navigation, magnetic pole drift is a valuable tool for understanding Earth’s internal structure. Variations in the magnetic field help scientists map the flow of molten metal within the core, offering rare indirect observations of regions that cannot be accessed directly. These insights improve models of Earth’s thermal evolution, plate tectonics, and long-term climate interactions. Magnetic studies also inform research on other planets, helping scientists compare Earth’s geodynamo with those of Mars and Mercury. In this way, tracking magnetic drift contributes to a broader understanding of planetary science.

Interesting Facts

- The North Magnetic Pole has moved more in the last 30 years than in the previous 100 years combined.

- Magnetic north and geographic north have never perfectly aligned throughout recorded history.

- Some animals, including birds and sea turtles, can sense magnetic field changes during migration.

- Earth’s magnetic field strength has decreased by about 9% over the last two centuries.

- Magnetic pole positions are updated regularly in the World Magnetic Model used worldwide.

Glossary

- Magnetic Pole Drift — the gradual movement of Earth’s magnetic poles caused by changes in the core’s magnetic field.

- Geodynamo — the mechanism by which Earth’s molten outer core generates the magnetic field.

- Magnetic Field — an invisible force field produced by moving electric charges within Earth.

- Magnetic Reversal — a long-term process in which Earth’s magnetic north and south poles switch places.

- World Magnetic Model — a global standard used to map Earth’s magnetic field for navigation and technology.