High temperatures present serious challenges for animals, especially those living in deserts or tropical environments. Surviving extreme heat requires complex physiological, behavioral, and anatomical adaptations. Animals must regulate their body temperature, conserve water, and often avoid direct sunlight. These survival strategies can vary significantly between species, depending on size, habitat, and activity level. Some animals become nocturnal to avoid daytime heat, while others rely on evaporative cooling mechanisms like sweating or panting. In extreme cases, some species can enter a state of aestivation, a kind of summer dormancy. These adaptations help animals maintain internal balance and avoid heat stress, dehydration, or death.

Behavioral Adaptations

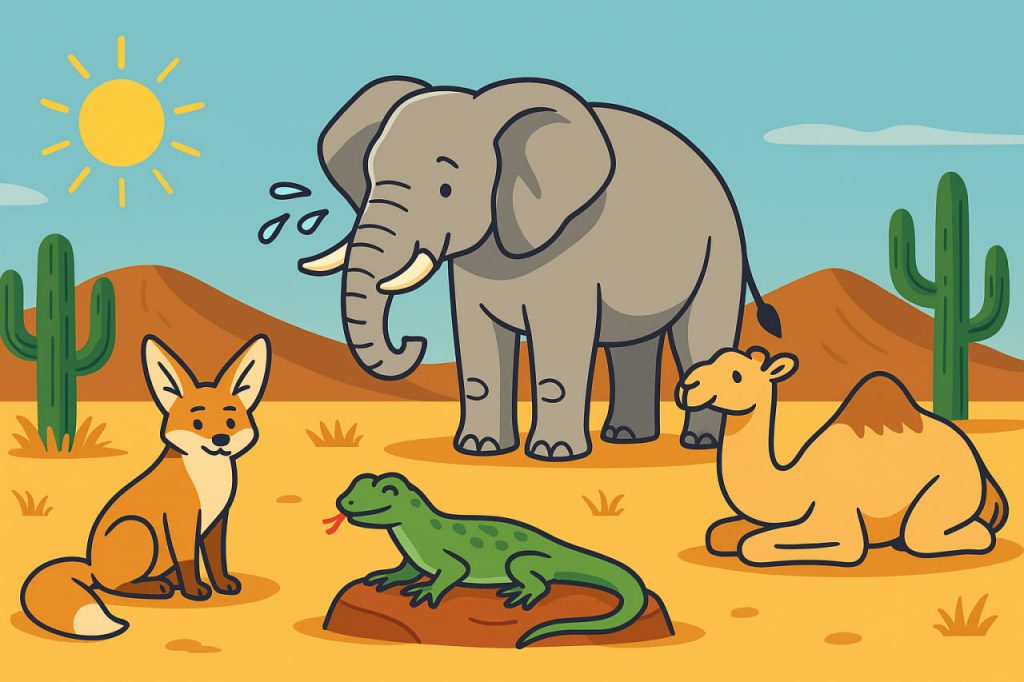

Many animals modify their behavior to reduce exposure to heat. For example, desert mammals like fennec foxes and kangaroo rats remain in burrows during the day and emerge only at night, making them nocturnal. Birds like vultures and eagles soar at higher altitudes where the air is cooler. Some species rest in shaded areas, reduce movement, or lie flat against cool surfaces to minimize heat absorption. Others, like elephants, use water bodies for bathing and spray mud or water over their skin for cooling. Reptiles often bask in the morning sun to raise body temperature and retreat to shade by midday. These behavioral changes reduce heat exposure and conserve energy.

Physical and Physiological Strategies

Animals also have built-in adaptations to manage heat. Large ears, like those of African elephants or jackrabbits, help release excess heat through increased surface area. Some animals have thin fur or light-colored coats to reflect sunlight. Birds and dogs rely on panting for cooling, while humans and horses sweat. Certain desert animals can survive without drinking water for weeks by extracting moisture from food and reducing urine output. Camels, for instance, can withstand body temperature fluctuations and store fat in their humps to minimize heat storage near vital organs. Lizards and snakes, being ectothermic, adjust their body temperature by alternating between sun and shade. These physical traits are essential for surviving in hot, dry climates.

Heat Tolerance and Climate Change

With global temperatures rising, animals must increasingly rely on their heat adaptations—or evolve new ones—to survive. Species that once thrived in moderate zones may now face heatwaves that surpass their tolerance. Some may migrate to cooler areas, but others are limited by habitat loss or mobility. Heat stress can reduce reproduction, impair immune systems, and cause mortality, especially in young or old individuals. Researchers are monitoring wildlife for signs of adaptation, such as changes in behavior, breeding patterns, or even body size. Conservationists are working to protect microhabitats, such as shaded forests and wetlands, that offer refuge during extreme heat. As climate change accelerates, animal adaptation to heat becomes not only a marvel of biology but a key factor in species survival.

Glossary

- Nocturnal – active at night to avoid daytime heat.

- Evaporative cooling – loss of body heat through sweating or panting.

- Aestivation – dormancy during hot and dry periods to conserve energy.

- Ectothermic – animals that regulate body temperature through external sources.

- Heat stress – physiological strain caused by prolonged exposure to high temperatures.

- Surface area – part of the body exposed to the environment, important for heat exchange.

Thanks for the auspicious writeup. It in reality used to be a leisure account it. Glance complex to more added agreeable from you! However, how could we be in contact?