In a rapidly changing world, wildlife faces one of its greatest challenges — fragmented habitats. Roads, cities, and agricultural lands often divide natural ecosystems, isolating animal populations. To counter this, scientists and conservationists have developed an elegant solution: ecological corridors, also known as wildlife corridors. These “green highways” reconnect nature’s broken landscapes and help species thrive in harmony with human development.

What Are Ecological Corridors?

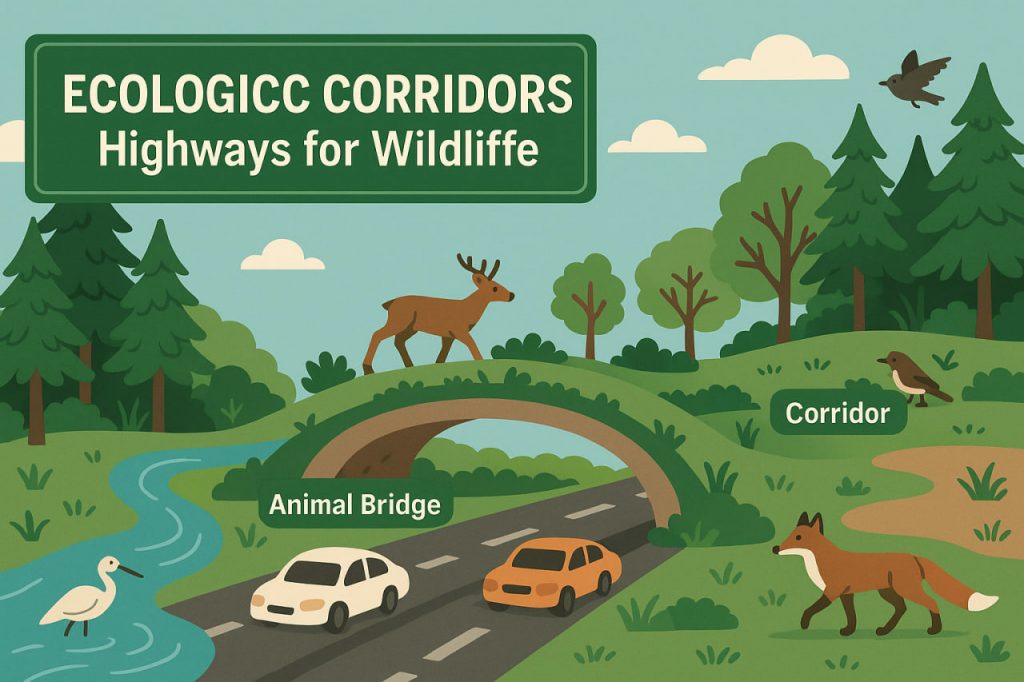

An ecological corridor is a strip of natural habitat that connects separate ecosystems, allowing animals, plants, and even microorganisms to move freely between them. These pathways can take many forms — forests, rivers, hedgerows, or even specially built bridges over highways.

They serve as lifelines for biodiversity, helping species migrate, find food, reproduce, and adapt to environmental changes.

Ecologist Dr. Amelia Brooks describes them as:

“Invisible threads that keep nature connected. Without them, ecosystems become islands — isolated and vulnerable.”

Why They Matter

When habitats become fragmented, animal populations are trapped in smaller areas, leading to:

- Loss of genetic diversity, making species more susceptible to disease.

- Reduced access to resources like water and food.

- Increased risk of extinction, especially for large mammals and migratory species.

Ecological corridors solve these problems by:

- Connecting habitats, allowing safe movement.

- Supporting migration routes, crucial for animals like wolves, elephants, and butterflies.

- Reducing human-wildlife conflict, by offering safer crossings away from roads and settlements.

- Maintaining healthy ecosystems, which stabilize climate and support pollination and seed dispersal.

Types of Ecological Corridors

- Natural corridors — rivers, mountain ridges, and forest strips that naturally connect habitats.

- Artificial corridors — human-made structures such as overpasses, underpasses, and reforestation zones designed to help wildlife cross developed areas safely.

- Stepping stones — small patches of green areas that act as “rest stops” for species moving between larger habitats.

Global Success Stories

- Banff Wildlife Bridges (Canada) — Overpasses and tunnels across highways have reduced wildlife collisions by over 80%.

- The European Green Belt — A massive ecological network running along the former Iron Curtain, connecting habitats across 24 countries.

- African Elephant Corridors — In Botswana and Kenya, protected migration routes have significantly reduced poaching and habitat loss.

Conservation biologist Dr. Leo Tanaka notes:

“Corridors are the future of conservation — they allow people and wildlife to coexist without one excluding the other.”

Challenges Ahead

Despite their importance, ecological corridors face threats from urban expansion, pollution, and poor land-use planning. Effective corridor design requires international cooperation, scientific research, and community engagement.

Interesting Facts

- Some birds use “aerial corridors” — wind pathways that help them migrate thousands of kilometers.

- Pollinators like bees and butterflies rely on flower-rich routes between gardens and meadows.

- In the U.S., the proposed Wildlife Corridor Conservation Act aims to protect migratory paths for over 2,000 species.

- Even underwater, marine corridors help fish and coral ecosystems recover from damage.

Glossary

- Habitat fragmentation — the division of natural environments into smaller, isolated sections.

- Biodiversity — the variety of life within an ecosystem.

- Migration routes — pathways animals follow seasonally for food or breeding.

- Reforestation — the process of planting trees to restore forests.