Water covers most of Earth’s surface, yet not all water is equally available or suitable for life and human use. While oceans dominate the planet, the vast majority of this water is salty and unusable for drinking or agriculture without costly treatment. Freshwater, by contrast, represents only a tiny fraction of Earth’s total water, but it is essential for ecosystems, food production, industry, and human survival. The balance between freshwater and seawater shapes climate systems, ocean circulation, and the distribution of life across the planet. Understanding how Earth’s water is divided—and how it moves between different reservoirs—is fundamental to understanding planetary stability. As population growth and climate change intensify pressure on water resources, this distinction becomes more critical than ever.

How Earth’s Water Is Distributed

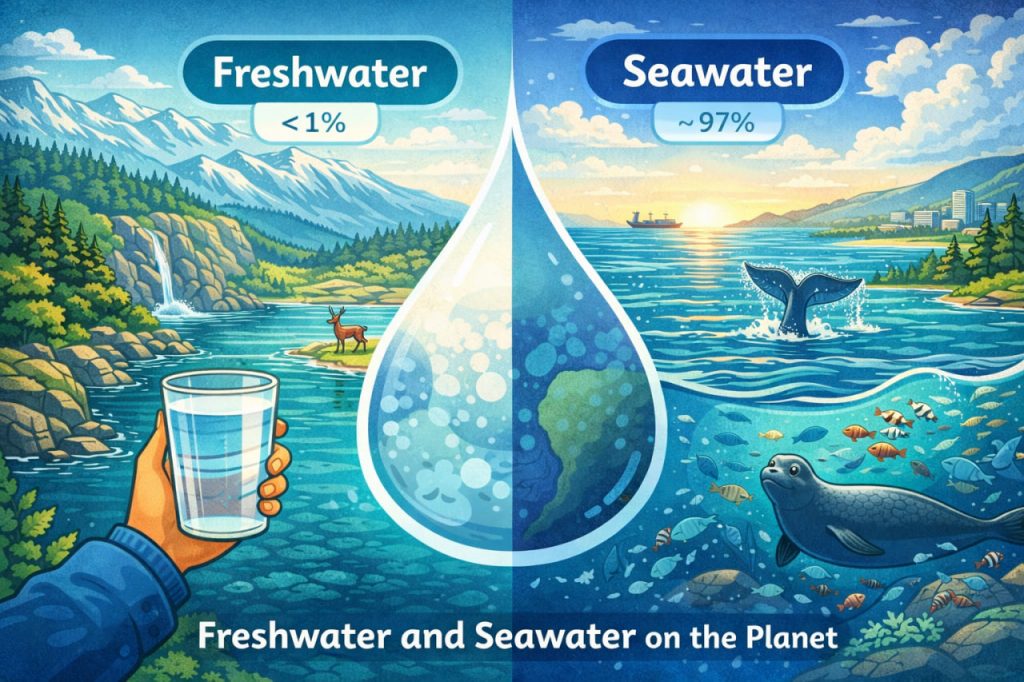

Approximately 97% of all water on Earth is seawater, stored in oceans and seas, while only about 3% is freshwater. Of this freshwater, nearly 70% is locked away in glaciers and ice sheets, primarily in Antarctica and Greenland. Another significant portion exists as groundwater, hidden beneath the surface in aquifers. Only a very small share—less than 1% of all freshwater—is readily accessible in rivers, lakes, and wetlands. This means that the water humans depend on daily represents a minuscule fraction of the planet’s total supply. According to hydrologist Dr. Caroline Hughes:

“Earth appears to be a water-rich planet,

but accessible freshwater is one of its most limited and vulnerable resources.”

This uneven distribution explains why water scarcity can exist even on a planet covered in blue.

Seawater and Its Role in Planetary Systems

Seawater plays a crucial role in regulating Earth’s climate and supporting marine life. Oceans absorb vast amounts of heat and carbon dioxide, helping stabilize global temperatures and slow atmospheric warming. Salinity affects ocean density, which drives thermohaline circulation—a global conveyor belt that redistributes heat across the planet. Marine ecosystems depend on the chemical composition of seawater, which supports phytoplankton, the base of the ocean food web and a major producer of Earth’s oxygen. Although seawater is not directly usable for drinking, it remains essential for climate balance, weather systems, and the planet’s long-term habitability.

Freshwater: A Limited but Essential Resource

Freshwater is vital for nearly all forms of terrestrial life. Rivers and lakes supply drinking water, support agriculture, and sustain freshwater ecosystems. Groundwater serves as a critical reserve, especially in regions with limited surface water. However, freshwater systems are highly sensitive to pollution, overuse, and climate variability. Droughts, melting glaciers, and changing precipitation patterns increasingly disrupt freshwater availability. Environmental scientist Dr. Miguel Alvarez explains:

“Freshwater systems respond quickly to human pressure.

Once damaged, they are far harder to restore than ocean systems.”

This vulnerability makes freshwater protection a central challenge for sustainable development.

The Water Cycle Connecting Fresh and Salt Water

Freshwater and seawater are not isolated systems; they are connected through the global water cycle. Solar energy drives evaporation from oceans, turning seawater into water vapor that later condenses and falls as precipitation. Rain and snow replenish rivers, lakes, and glaciers, eventually returning water to the ocean through runoff and groundwater flow. This continuous circulation redistributes heat, nutrients, and energy across the planet. Disruptions to the water cycle—such as increased evaporation due to warming or altered rainfall patterns—can upset the balance between freshwater and seawater systems, affecting both climate and ecosystems.

Why the Balance Matters for the Future

The balance between freshwater and seawater underpins food security, biodiversity, and climate stability. Rising sea levels threaten to contaminate coastal freshwater sources with saltwater intrusion. At the same time, growing demand for freshwater increases reliance on technologies such as desalination, which come with environmental and energy costs. Protecting freshwater ecosystems, improving water efficiency, and maintaining healthy oceans are interconnected goals. Managing Earth’s water wisely will play a decisive role in humanity’s ability to adapt to climate change and ensure long-term planetary resilience.

Interesting Facts

- Less than 1% of Earth’s freshwater is easily accessible for human use.

- Oceans store about 90% of the excess heat generated by global warming.

- Phytoplankton in seawater produce over half of Earth’s oxygen.

- Groundwater supplies drinking water for nearly half of the world’s population.

- Saltwater intrusion is increasing in coastal aquifers due to rising sea levels.

Glossary

- Freshwater — water with very low concentrations of dissolved salts, found in rivers, lakes, and groundwater.

- Seawater — salty water found in oceans and seas, containing dissolved minerals and salts.

- Thermohaline Circulation — global ocean movement driven by differences in temperature and salinity.

- Aquifer — an underground layer of rock or sediment that stores and transmits groundwater.

- Water Cycle — the continuous movement of water between the ocean, atmosphere, and land.